A Written History

November 26, 2017

The home my parents left after they died is a warm place full of memories, both physical and not, and one day, the year after my mom died, my sister and I set about the task of cleaning out her room.

Mama was not a hoarder, but she was sentimental. Drawers and boxes and shelves were filled with newpaper clippings, cards and letters. Hundreds of them— obituaries, wedding announcements, birthday cards, Christmas cards, and just plain letters.

I am, by nature, a nosy person, so I read each and every one. Some were yellowed and fragile, their folds delicate, their ink faded. Others looked as if they’d just been written days before. There were homesick notes from her Uncle Jimmy to her mother during World War II, excited postcards from her twin brother after his move to Chicago in the 1950’s, rambling nothings from me over the decades, cards and letters from my siblings as they traveled the world, and regular Christmas updates from various friends with whom Mama and Daddy had stayed in contact over the many years. Perhaps most surprising was a letter to my mother from a man on a ship to Korea during the war. It was signed simply, “Red.” Mama, to my recollection, had never mentioned him, and no one I question has any knowledge of him. That he loved my mom, though, was apparent. I’ll never know whether she loved him, too, or what happened to him.

As my sister and I combed through these letters, I realized that they narrated a history of this country and of my family. It wasn’t the history found in textbooks or the typical family story that gets passed from generation to generation — who married who and what children they had or who went to what school or owned what land or business. These letters were the details of the story. They were the worries of the men in the trenches, not the maneuverings of the generals who put them there. They were the aspirations of Southerners moving north where the jobs were. They were the daily struggles and victories, the heartbreak and the hopes. They were the voices of people no longer with us and people we no longer were.

With that realization, my heart broke a little. In this digital age of texts and e-mails, Facebook and Twitter, dick pics and Tinder, our history disappears with a swipe. (Mind you, with some things, that’s good. Dick pics? Really?) Other than social media posts, though, we will have no written story. Written letters are so often full of detail that we never share publicly, emotion we reserve for those closest to us, and scrolling a few years back through Facebook or IG for a stroll down memory lane isn’t practical. When I read my dad’s letters that he sent to me, I am holding a thing he held first. I feel the indentions in the paper that his pen placed there. I am transported to a time when he was still here. For a few moments we are only as far apart as that piece of paper.

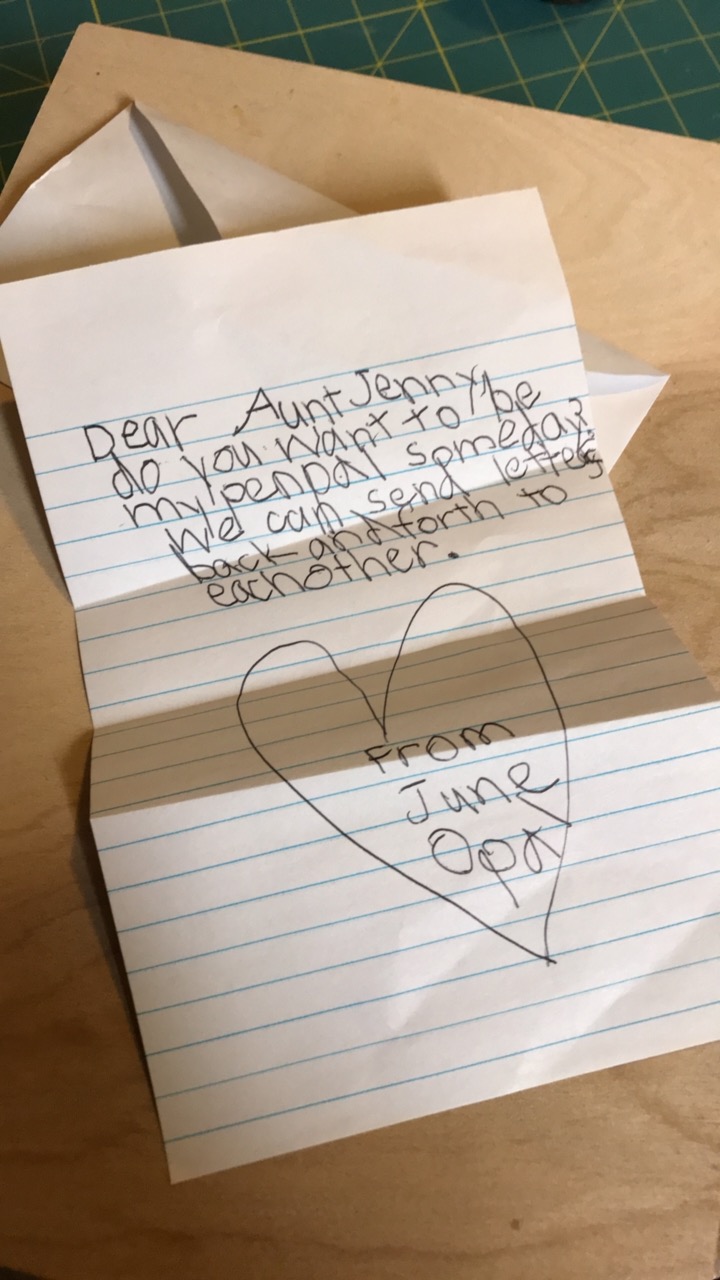

So, yes, I still write “real” letters and send them by post. Occasionally I even receive one. When my great niece sent me the letter in the picture that graces this post, I was thrilled. Of course I’ll be her pen pal. And maybe we’ll keep writing the history of this family.

*****

This story and all related material are the original works of Estora Adams. All rights reserved.